Authored by Christian Wappl

Striking a Balance: Invasive* Species Management in a Changing World

How Did We Get Here?

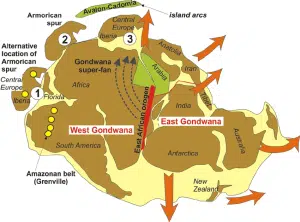

Animals have arrived in new places and established populations since time immemorial without being considered invasive species. What we think of as a pristine, untouched ecosystem is the result of the original native species and countless later arrivals duking it out for millions of years. For example, New Zealand’s flora and fauna was long thought to be descended from whatever was around when New Zealand broke off from Gondwana some 80 million years ago.

However, the fossil record of plants showed without a doubt that almost no plant families were continuously present on the islands since then. Furthermore, many plant families such as grasses and daisies evolved after the split and therefore could only have arrived by crossing the ocean. Even groups typical of New Zealand such as southern beeches arrived a mere 30-40 million years ago. Similar origins are hypothesized for some animals such as the kiwi, but the fossil record here is poorer and therefore this is more speculative. What is clear is that there has been a significant turnover of species long before the first humans set foot in New Zealand. Therefore, an ecosystem that is in a perfect state and must be conserved exactly as-is does not and has never existed.

That being said, the veritable flood of species shipped around the world nowadays is a completely different beast from the usual slow trickle of naturally immigrating species over time. Furthermore, animals that reached remote islands used to fall into specific categories. They were, for the most part, small generalists that could either fly, swim, or cling to vegetation floats. Among vertebrates, birds and reptiles were favored over mammals and amphibians. For example, it was unlikely that a voracious, mid-sized mammalian predator such as a cat or stoat (let alone multiple species) could have ever established a population in New Zealand by natural means, and yet cats, ferrets, stoats, and weasels were established in rapid succession thanks to human efforts. In the 1800s, acclimatization societies spread European species around the world in a bid to make settlers feel more at home in the foreign lands. Initially, they focused on birds and game animals, with predators being introduced later in a bid to keep the out-of-control rabbits in check.

A Balanced View

We’ve come a long way since then. Today, invasive species are regarded as ecological troublemakers and their control and eradication have long been a main focal point of conservation efforts worldwide. There can be no doubt that some invasive species (notably feral cats and pigs) have done tremendous harm to vulnerable ecosystems and even played a role in eradicating entire species. However, not all invaders are created equal. In this article, I’ll explore the complexities of invasive species, shedding light on their impacts and advocating for a more nuanced approach to their management.

Two factors are particularly important in determining the severity of impact of an invasive species. The first is the remoteness and size of a habitat. Islands and other secluded ecosystems such as lakes, plateaus and mountain tops are usually more vulnerable to invasive species than large contiguous ecosystems such as plains or oceans. Not only do invaders inflict higher damage in such locations, but eradication is also far more feasible in a limited area. New Zealand’s Predator-Free 2050 program, which aims to eradicate non-native predatory mammals, is one such promising approach.

Brown tree snakes devouring Guam’s birds. Rats and cats devastating land bird, mammal and reptile populations in Australia and New Zealand. Goats destroying native vegetation on islands around the globe. The blood-sucking larvae of Philornis downsi flies killing songbird nestlings on the Galápagos

Islands. These and many other of the most damaging invaders have one thing in common: they were unlike anything native plants and animals had previously encountered. This allowed them to wreak havoc on native ecosystems, sometimes even driving entire species extinct. The second important factor to consider is therefore the previous occurrence of similar species.

In contrast to the previous examples, native animals in Europe are familiar with the concept of ground-dwelling mammalian predators, and accordingly, there is little evidence that the raccoon – originally native to North America – is detrimental to its prey species or strongly impacting native predators via food competition. Certainly, no species is in acute danger of going extinct due to it.

For the raccoon and other invasive species in widespread and robust ecosystems, we should consider if eradication is feasible, and even if it is: maybe the money could be better spent elsewhere. A functioning but altered forest is better than one where old-growth trees have been logged and the insects poisoned, but that is free of alien species.

Grey vs Red

Consider the grey squirrel in Great Britain: introduced from North America in the 1870s, it has become ubiquitous throughout most of England and Wales. Remnant populations of the formerly plentiful native red squirrels survive mainly in parts of Scotland and Ireland. For many, the case is clear: the invasive grey has out-competed the native red through resource competition and disease transmission. To restore balance the invader must die, and the native be restored.

The reality is much more complex: the British Isles have been altered by prehistoric human species for almost a million years, with modern man arriving some 40,000 years ago. Over the millennia, habitats were degraded, and many native species were extirpated from the isles. By the time the grey squirrel arrived, it encountered severely weakened ecosystems and spread like wildfire. Arguably, if British forests were in better condition, the greys would never have been able to out-compete the reds to this extent. Evidence for this was found in a study that investigated the impact of a now rare predator, the pine marten, on squirrel populations. There appeared to be a strong negative effect of the predator on the invasive species, but the native species thrived when cohabiting with it.

And what’s more: would the red squirrel disappearing from the British Isles and being replaced by the grey squirrel really be an ecological disaster of such enormous magnitude that we should funnel our time and money into preventing it? The red squirrel is common throughout its enormous range from Spain to Korea, and it shares its genus with over two dozen closely related species. It is in no danger of going extinct anytime soon, and even if it did – by no means could it be considered a unique offshoot of the tree of life. The grey squirrel would evolve to fully fill the niche previously occupied by the red squirrel, and the British ecosystems would be scarcely any different in the long run.

New Problems in New Caledonia

Now compare this to the plight of the Kagu on the island of Grand Terre, New Caledonia. Like the red squirrel in Great Britain, this medium-sized bird is threatened by invasive species and habitat loss. However, the Kagu does not occur elsewhere in the world, and what’s more: it has no close relatives. It is the sole survivor of an entire family of birds and one of only two survivors in its order. For comparison: us humans share our family with seven species, and our order with over 300 species. The extinction of the Kagu would mean the removal and cauterization of a whole limb of the tree of life.

The invaders threatening the Kagu – dogs, cats, pigs, and rats – also endanger a whole slew of other species in the rainforests of New Caledonia, and possibly the very integrity of the ecosystem. In contrast, grey squirrels have not been found to negatively affect bird populations and there is little evidence that they are the main culprit for the negative effects Britain’s ecosystems are currently experiencing.

In an age of limited funds and unlimited threats to biodiversity, surely it would seem more prudent to focus on conserving unique species such as the Kagu instead of trying to save every small population of common taxa such as the red squirrel?

* When it comes to species introduced abroad by humans, adjectives such as non-native, exotic, foreign, introduced, naturalized, invasive and many more are thrown around. Many of these definitions overlap significantly and are also subject to change. In this article, I will therefore focus solely on invasive species – defined as species that established themselves in a novel habitat with human help (consciously or otherwise) and are now causing damage to native ecosystems and species, or to human interest.

See more of Christian’s work at his website or on his Instagram @christianwappl

Comments (0)