Authored by Michael Graziano, Ph.D. Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata): they’re instantly recognizable, charismatic, and…

4.

Secret Love Affairs of a Rediscovered Toad – Pt. 1

Part 1

Text and Photos by Ross Maynard

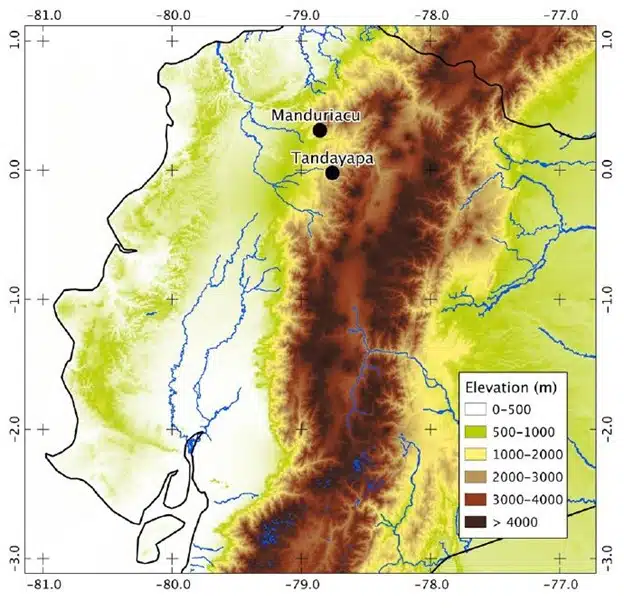

Species don’t get rediscovered very often so this is a story that is near and dear to our hearts. Not long ago, the Tandayapa Andes Toad (Rhaebo olallai) was among the most rare and poorly understood amphibians in the world. For decades it was known from a lone museum specimen collected in 1970 from the western slopes of Andean Ecuador. And even this unique specimen went unnoticed for well over a decade floating in a museum specimen jar in London before it was finally recognized as an undescribed species. In fact, 15 years would pass from the time it was collected before the species would be formally described to science and 43 years before it was rediscovered.

As a side note, although it took 15 years for the Tandayapa Andes Toad to be described from the time it was collected, the average time it takes from collection to description of a species is 21 years, which is known as a species’ “shelf life.” The Biodiversity Group, for comparison, has so far averaged around three years from collection to description, as reducing the time for a species to be described is paramount when a species’ future is already jeopardized by the time they are discovered (example).

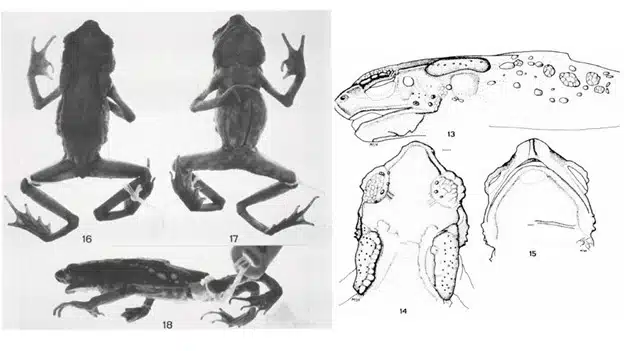

At any rate, in the years following its introduction to the scientific community, various attempts to find more individuals near to where it was originally found came up empty-handed. Decades went by where someone could communicate the entire body of information known about this toad in a short elevator ride: the female specimen measured 39.6 mm long, the contents of her stomach revealed that she had eaten some ants and two beetles, and the specimen was known to have been collected somewhere near the town of Tandayapa on the western Andean slopes of Ecuador at an elevation “probably between 1400 – 1600 m.” Perhaps an enthusiastic communicator might also note that it was thought to be most closely related to two other recently described species of Andean toads at the time, both of which were equally rare (okay, one of them was actually known from TWO specimens).

In other words, no males, little toadlets, or tadpoles had been documented. Nothing was known about its behavior, mating call, range in body size, or habitat requirements. And no images of a living individual existed. The only person that had been fortunate enough to see one alive was the collector of the “type specimen,” Jorge Olalla, and to whom the species’ patronym honors. Members of the Olalla family were known to collect scores of animals to sell to international museums and universities, and the vague information associated with the type specimen suggests that the experience of finding this lonesome lady toad stood out no more than coming across any other small, drab animal.

More than four decades after the first specimen of the Tandayapa Andes Toad was collected, two adventurous conservation biologists living in Ecuador decided to explore a remote property situated 40 km north of Tandayapa (as the crow flies) in 2012. The justification for this adventure was simple: as with many remote pockets of habitat within the Andes, it was bound to be an untapped biological treasure chest. When the lot was purchased a few years prior by one of our colleagues at Fundación Cóndor Andino (Andean Condor Foundation), he had purchased it without ever having stepped foot on the land, as a quick look through binoculars from the nearest town seemed to indicate that it checked the only boxes that concerned him: it was caked in lush primary forest, cheap, and seemingly removed from any immediate threats as it’s situated within a rugged river canyon. Since buying the plot, he had only hiked in to see the forest a couple times to scope it out and meet some of the locals living in a small community lower down in the canyon. But for this adventure, he had convinced his friend and conservation biologist working for The Biodiversity Group *, Ryan Lynch, to tag along. To be sure, the process of “convincing” Ryan included a bullet-point or two of relevant information and absolutely zero arm-twisting.

After leaving Quito early on the morning of 18 November 2012 and arriving at the nearby community of Santa Rosa de Manduriacu a few hours later, the duo geared-up and began the challenging trek towards the bundle of hovering clouds obscuring the mysterious forest ahead—the area is characterized by frequent downpours and, at the time, poorly maintained trails that zigzagged along the river canyon’s slope. After hours of slogging through deep mud and persistent rain with heavy packs strapped to their backs, they arrived at a small clearing where an old wooden shelter stood that they used as their base camp. After a little rest, the distinct smell of the thick, humid air of the Andean forest and the view from the cabin looking over the forest canopy was all they needed to re-energize for a night of sampling the narrow montane streams that flow down-slope to the raging Río Manduriacu below.

Within minutes of searching, their efforts were handsomely rewarded as the beams of their flashlights focused in on numerous unusual toads propped up on the leaves draped alongside the cascading stream. There were colorful tiny toads and larger, lanky-legged brown toads, which they couldn’t identify or tell if they were of the same species. Regardless, they knew it was certain to be an important observation and was exactly the type of discovery they were hoping for!

Oozing with curiosity after finding something so remarkable in just a single night, they headed back to Quito with images on hand to try and pinpoint what species they had observed, if even described at all. After months of researching the literature and questioning colleagues at local universities, they finally found their answer. Lo and behold, they had not only rediscovered the Tandayapa Andes Toad after nearly forty-three years, but this was the first time ever that juveniles and males had been documented!

The mystery continues in part 2, stay tuned!

* Ryan Lynch now works as the Executive Director of the conservation nonprofit, Third Millenium Alliance, and continues to collaborate with The Biodiversity Group in Ecuador. Sebastian Kohn still owns the plot of land that would become officially known as the Río Manduriacu Reserve in 2018, which his NGO co-manages along with Fundacion EcoMinga. The efforts of both organizations have successfully expanded the reserve’s boundaries in recent years, with one of their most significant assets in that process being the data collected and published by The Biodiversity Group.

*disclaimer* This blog article was prepared by the author in their own personal capacity. The opinions in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Biodiversity Group.

Comments (0)