Part 2 Text and Photos by Ross Maynard Positive conservation news can be hard…

6.

The Checkered Past of a Spotted Turtle

Authored by Michael Graziano, Ph.D.

Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata): they’re instantly recognizable, charismatic, and have been the focus of many a hobbyist, conservationist, and scientist. Across their range, many areas have been set aside and protected simply because they occur there. They’re high profile and are protected by most states, and yet, they continue to decline and have an uncertain future in many areas. While they may not seemingly be a candidate for Life Overlooked, there is something missing from what should otherwise be viewed as a success story. So, what is it?

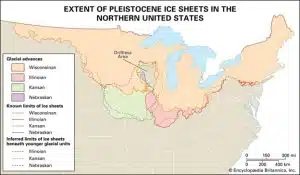

Let’s begin with some general background information on our focal species. Spotted turtles have a range that extends from Florida along the Atlantic coast north to Maine, and west to Illinois along the Great Lakes. Across that range, you’ll find them inhabiting everything from ephemeral wetlands, floodplain marshes, streams, man-made ditches, swamp forests, cranberry bogs, calcareous fens, wet prairies, and even bodies of water that can only be described as polluted (see below). Herein lies dilemma: these are mobile animals that use a variety of habitats throughout their life history. It may seem odd that a four-to-five-inch turtle would be so prone to live a nomadic life. Not only is it accurate, but this mobility has largely been a secret to their success. During the most recent glacial period – the Wisconsin glaciation – which existed until approximately 11,000 years ago, much of the current range of spotted turtles was beneath a sheet of ice

How does this behavior factor into the current plight of the spotted turtle? As mentioned earlier, their mobility is not only a secret to their success but also their Achilles’ heel. Spotted turtles are wanderers. While many individuals exhibit high site fidelity, they still move. They may overwinter in an ephemeral wetland, a shallow stream, or within the submerged roots of a tree. Upon resuming activity in the early spring, they begin to search for mates.

Even when the threat of mortality resulting from movements of their annual life cycle is put aside, there are other anthropogenic threats. Obviously, collection for the pet trade is a serious threat, and many populations have been extirpated as a result of the activities of unscrupulous collectors. Scientists from the days of old, where collecting numerous voucher specimens was the way of the world, are also not without blame.

So, herein lies the problem: both the secret to success and the silver bullet to conserving the charismatic, high-profile spotted turtle are found in behavior – both theirs and ours. Legally protecting a species is a good start, but not sufficient by itself. Protecting a single patch where that species occurs is also insufficient in maintaining a population. We have seen this in action, and it has failed. In order to foster a population, we must protect not only their critical habitat, but the habitat that connects it. We will have to commit to setting aside larger tracts of land encompassing a mosaic of habitats. This will benefit not only spotted turtles, but many other organisms. Further, we must encourage a change in narrative for protecting lands harboring threatened species: not all protected lands should welcome public access. Not all wetlands need a boardwalk bisecting them so that we are able to access the interior regions.

What does this all mean? What is the take home message from this reading? Organisms can be in the spotlight, they can receive protection, they can be given land to inhabit, but they are still essentially Life Overlooked. You have to look at the totality of the organism’s behavior in order to successfully preserve it. You can push the charismatic spotted turtle into the conservation spotlight and invest resources into preserving them, but if you overlook the seemingly menial aspects of their complex life history your efforts are likely doomed to failure. It is because of this that close observation and research on the local scale, like what The Biodiversity Group and its alliance supports, is of continued importance.

*disclaimer* This blog article was prepared by the author in their own personal capacity. The opinions in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Biodiversity Group.

Comments (0)