Authored by Michael Graziano, Ph.D. Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata): they’re instantly recognizable, charismatic, and…

3.

Cryptic Species Conservation

Authored by Michael Graziano

What is a species? It’s a seemingly simple question that you would think has a simple answer. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case. Over the years, the definition for what a species is has evolved, with Ernst Mayr’s definition being at the forefront: essentially, organisms may be considered the same species if they can produce fertile offspring. Unfortunately for many of us, that definition comes with a good amount of fine print – particularly where plants are concerned. Many plants have hybrid origins – the interbreeding of two different species – which are fertile (oaks and orchids are two particularly guilty parties!). I’m certain that this watered-down explanation of what a “species” is will garner some criticism but discussing the species concept is not the objective of this writing. Rather, let’s instead focus on how molecular techniques used in designating cryptic species have been used to enhance conservation.

Let’s first look at “cryptic” species – species which aren’t hiding deep underground or in some remote forest, but rather an organism whose presence is known to us, but we have not yet recognized as representing numerous species. As a result, many organisms are somewhat crudely lumped as being the same species because they exhibit a large range, or simply haven’t been investigated close enough.

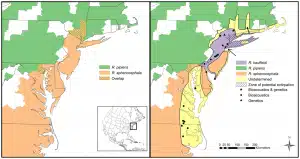

A particularly egregious example of this is observed in the Atlantic Coast Leopard Frog (Lithobates kauffedli) – a frog only formally described in 2014 yet whose range encompasses the most densely populated region in the United States: the coastal regions of Baltimore, Maryland through New York City and Long Island (Fig. 1)! Originally thought to be either the Northern or Southern Leopard Frog (L. pipiens and L. sphenocephala, respectively), this designation is supported by molecular and bioacoustic data and yields an important consequence: legal protection and access to funding. As mentioned in the previous post, conservation measures are often focused on rare or localized species, overlooking those seemingly “common” organisms. However, establishing that in some cases one wide-ranging species actually consists of multiple cryptic species is oft times a first step in conservation.

Molecular genetics has been critical in identifying these cryptic species, whose identification is nearly impossible without them. The result of this comes with the realization that, in some cases, certain populations aren’t actually declining populations of an otherwise common species but represent a distinct and possibly imperiled species. The Flatwoods Salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum) (Fig. 2) was until recently considered one rare species localized in the southeastern coastal plain of the United States. However, in 2007 it was found that this “species” was comprised of two different species: Frosted Flatwoods Salamander (A. cingulatum) and the Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander (A. bishopi). This designation has proven to be of critical importance to the conservation of each species, with both being listed as either federally threatened or federally endangered, thus requiring them to be researched, managed, and funded as two distinct species instead of one.

Another result of identifying these cryptic species includes greater insight to the history and current status of those species – including the ability to more finely-tune conservation efforts. Local-scale management often proves more successful as it can better adapted to the regional variations frequently observed in populations.

This is particularly visible in the case of the Alligator Snapping Turtle – once thought to be a single species it is now known to represent three distinct species (Macrochelys temminckii, M. suwanniensis, and M. apalachicolae). Recognizing these three different species has provided conservation officials with the ability to better determine management plans for this threatened turtle. For example, alligator snapping turtles have historically faced the challenges of overexploitation resulting in some populations which are severely depleted. With the recognition of the three distinct species – two of which are largely restricted to just a handful of river systems in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama – came the ability to establish conservation efforts that best serve each species, including enhancing state laws.

What better examples of life overlooked are there than these sorts of cryptic species? If this topic fascinates you, I’d recommend that you look into the Jefferson and Blue-spotted Salamander complex (Ambystoma jeffersonianum and laterale), the Eastern and Western Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus and S. tergeminus) (Fig. 3), as well as the Nodding Lady’s Tresses Orchid complex (Spiranthes cernua) (Fig. 4), and . Regardless of whether a population represents a genetically distinct species (and in many cases, they do not), maintaining the genetic integrity/diversity of organisms is just as critical as maintaining large population sizes. The next time you’re out on a hike and spot something you’re normally quick to overlook – just remember, you might just be looking at a yet-undescribed species.

*disclaimer* This blog article was prepared by the author in their own personal capacity. The opinions in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Biodiversity Group.

Comments (0)