Authored by Michael Graziano, Ph.D. Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata): they’re instantly recognizable, charismatic, and…

5.

Secret Love Affairs of a Rediscovered Toad – Pt. 2

Part 2

Text and Photos by Ross Maynard

Positive conservation news can be hard to come by, so when a species that was thought to potentially be extinct is rediscovered, it’s invigorating news to the conservation community! But the real value of such an event extends well beyond a mere reprieve from the more usual narratives of never-ending environmental challenges that cause so many of us to struggle with ecological grief. Finding a long lost species presents a unique opportunity to study the species and also implement measures to protect their futures.

Such opportunity is exactly what arose following the rediscovery of the Tandayapa Andes Toad in Ecuador. And it prompted decisive action!

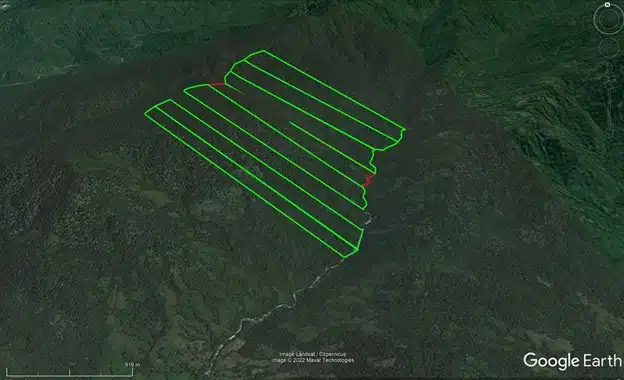

Shortly following their landmark discovery, the property was registered in a program that supports land owners that maintain their forest, and a few years later, an Ecuadorian NGO took on management of the forest and began developing initiatives to support the local community. To date, these actions have resulted in the employment of several local community members as well as the purchase of numerous adjoining parcels that now encompass over 1,200 hectares of contiguous Andean forest that is regularly patrolled by reserve staff. It’s thanks to these actions that the lush Andean forest on the western slope of the canyon is now formally known as the Río Manduriacu Ecological Reserve.

Also organized after the rediscovery were expeditions spearheaded by our team aimed at learning more about the toad, its habitat, and the species living alongside them. Beginning with the first official expedition to Manduriacu in October 2016, our ongoing efforts at the reserve have yielded a number of exciting findings. As a result, the time needed in the metaphorical elevator ride to communicate everything known about this toad has become much longer than it was before!

To take just a quick peak at what has been learned, we now better understand details such as the size, color, and pattern of different age classes of the toad, as well as their behavior, habitat, and evolutionary relationships. For example, we know that females can grow to be longer than the diameter of an American billiard ball, whereas the strikingly attractive juveniles can be as tiny as half the diameter of a nickel. The toads are only found within mature forest, love to use low-lying perches in the vegetation adjacent to pristine montane streams, can climb nearly-vertical surfaces such as tree trunks and wet boulders, and are absent at the highest reaches of the reserve. We’ve even been fortunate enough to witness two males in combat!

But one of the more important steps our team took was to use our data to formally list the toad’s global conservation status on the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered, thereby elevating the species to the forefront of the conservation radar. Prior to this, there wasn’t enough information known about the Tandayapa Andes Toad (Rhaebo olallai) to assess it (meaning its prior listing was tabbed as Data Deficient).

However, even though we’ve learned a lot about this remarkable toad, there’s still some important knowledge gaps to fill. For instance, we’re still trying to figure out where they’re hiding their babies (yes, the tadpoles). And it’s not from lack of effort. Whether searching in the dry season, wet season, big streams, little streams, stream pools, phytotelmata (e.g., tiny pools of water in bromeliad axels), or temporary pools, the results have been the same: nada. Although little toadlets can be among the more common observations recorded during an expedition, which presumably have recently metamorphosed from the tadpole stage, none of them have been found with even a hint of their tails remaining from that process. Allocating some dedicated time to finding their tadpoles is certainly in order, and we think we have a hunch as to where we might need to look a little more carefully!

This brings up another mystery: despite seeing loads of adults over the years, nobody has seen a male and female in amplexus (what big toads do when they want to make tiny toads). Fortunately, we have been able to record the melodic mating call of the males, but the few times we’ve seen or heard them calling, it only appeared to be effective at wooing us instead of any female toads. It’s a bummer considering that if we could find a pair in amplexus, we could then sneak around and observe their love affair around to see exactly where they deposit their eggs, which is where those hidden babies will develop.

The reasons for wanting to know these bits of information about the intimate lives of threatened species are numerous, but most notably as they are critical to devising effective conservation management strategies for the long-term. If we are to prevent a species from going extinct, it’s critical to understand what micro-habitats are necessary for them to develop and survive. Unfortunately, knowing little about the reproductive behaviors of uncommon species is quite common. Nonetheless, it’s these types of questions that leave us anxious to continue our work at the Río Manduriacu Reserve and elsewhere. (Remeron) In the meantime, we look forward to sharing how our experiences have yielded other truly remarkable discoveries about the many forms of life living alongside the Tandayapa Andes Toad, including species that were previously unknown to science!

*disclaimer* This blog article was prepared by the author in their own personal capacity. The opinions in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Biodiversity Group.

Comments (0)